What is the Role of Private Equity?

Over the past two and a half decades, private equity has evolved into an increasingly important strategic asset allocation consideration for both institutional investors and high net worth individuals. Private equity offers investors the potential for both enhanced returns relative to public markets (i.e., return premium”) and diversification benefits in terms of risk reduction. The justification for this return premium relative to public markets is based on the increased liquidity risk and investment risk associated with private equity investments. The diversification benefits of private equity investing derive from an expanded investment opportunity set, including exposure to less established companies and nascent industries which are not publicly-traded. Lastly, there are regions (e.g., emerging markets) where private equity investing may provide superior access relative to public markets.

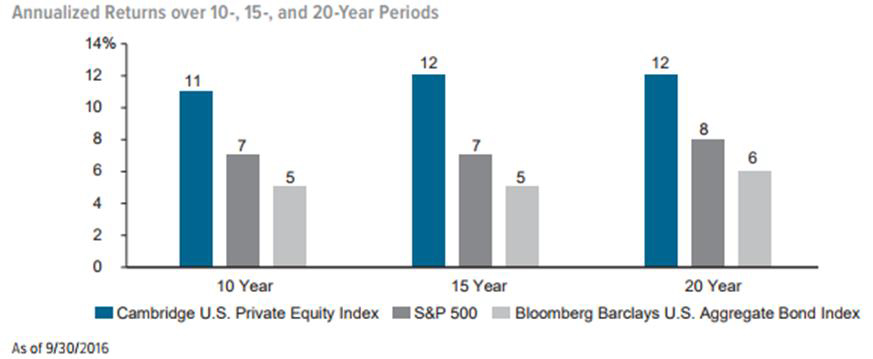

As detailed in Figure 1, the returns of private equity investments have historically exceeded the returns of both public equity and public fixed income markets by several percentage points both short-term and long-term periods.

Figure 1: Return History of Select Asset Classes

Source: Bloomberg; Cambridge Associates

How does Private Equity Investing Work?

Private equity investing is similar to public equity investing in certain ways yet different in other ways. In both public and private equity investing, an investor owns equity (i.e., “stock” or an “ownership interest”) in a company. However, the size of the ownership interest could be small (“fractional” or “noncontrol”) or large (“control”), and that ownership interest could be directly acquired or indirectly acquired. For example, in public equity investing, an investor might buy 100 shares of Coca-Cola stock. That investor Source: Bloomberg; Cambridge Associates 2 has directly acquired a fractional ownership interest in a publicly-traded company. This fractional ownership interest implies less than full control. Conversely, in private equity investing, an investor indirectly acquired a controlling ownership interest in a privately-held company.

Exposure to private companies is typically achieved through a special purpose vehicle known as a limited partnership (“LP”), whereby a limited partner commits a fixed amount of money (“committed capital”) to the LP and delegates investment authority to a general partner (“GP”). The GP then requests (i.e., “calls”) this committed capital over several years, investing it in a portfolio of underlying companies which are thereby privately owned. The primary objective of the GP is to acquire a company and increase its underlying value. The GP can achieve this through various means, including operational enhancements and/or corporate restructuring. Ultimately, the GP seeks to enhance the value of the company in order to sell it a future date for a material profit. A portion of this profit is then passed through to the LP investor.

Key Characteristics of Private Equity

Private equity has several unique characteristics that investors should evaluate when considering whether this type of investment is suitable for inclusion in their portfolio. Specifically, any investment should be consistent with an investor’s unique return objective and tolerance for risk, as well any investor specific constraints (e.g., liquidity needs, time horizon, tax considerations, prohibited investments, etc.).

The key characteristics of private equity include:

Illiquidity – Investments in private equity are illiquid, meaning that the underlying investment cannot be readily sold on a securities exchange. Moreover, private equity investing is illiquid at both the limited partnership level and at the security (i.e., company) level. As a result of this illiquidity, private equity investing is more suitable for long-term investors, with most limited partnerships lasting at least ten years. The illiquidity is also due to the private equity fund structure in which capital is invested in the initial years and returned over the subsequent time period as valuation enhancement materializes.

Valuation – The valuation of private equity investments differs from public equity investing in both calculation frequency and methodology. In public equity investing, calculation frequency is daily and methodology is market-based, whereas in private equity investing, frequency is quarterly and valuation is appraisal-based. As a result, private equity has exhibited a historically lower realized volatility relative to public equities. Nevertheless, this lower historical volatility does not necessarily imply lower risk.

Complex Fee Structure – Private equity fee structures are significantly higher relative to most public equity investment vehicles. Additionally, private equity fees typically include two distinct layers, a management fee and a performance-based fee. Management fees typically range between 1.0% and 2.0% on committed capital, while performance fees (i.e. “carried interest”) typically range between 10.0% to 20.0% of profits above a return rate, usually 8.0% annualized. 3 Private equity managers attribute the higher fee structure to the resource intensity of this type of investing, and also to the requisite skill associated with increasing the value of an underlying investment.

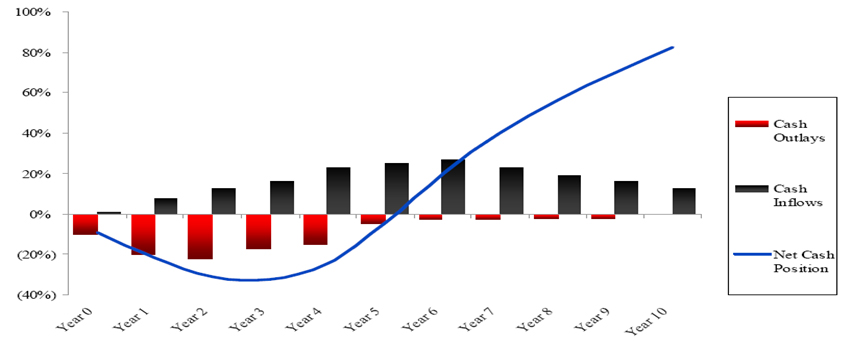

Irregular Cash Flows – Investors in private equity will experience irregular cash flows associated with this type of investing. The cash flow profile is referred to as a “J-Curve”, where there are negative cumulative cashflows during the initial five years of the limited partnership, followed by positive cumulative cashflows during the latter years of the limited partnership. As a result, performance is often negative during the early years of the limited partnership and ultimate fund evaluation is not possible until later years. The “J-Curve” can be seen in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2 – The J-Curve

Categories of Private Equity

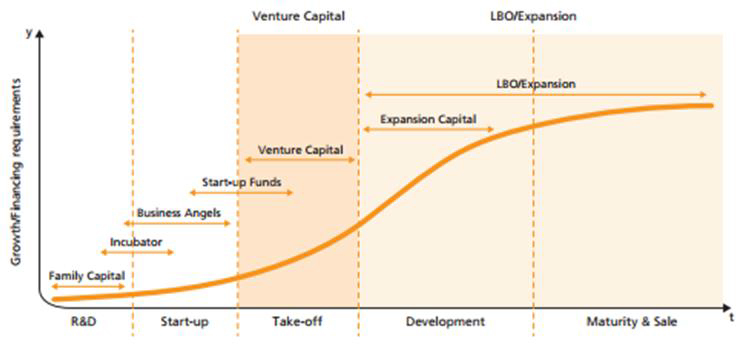

There are several distinct strategies within the broader private equity universe. Strategies are often classified according to a company’s growth lifecycle. Some of the most common private equity investment strategies include:

Buyout – Occurs during all phases of growth where financial leverage, enhanced corporate governance and operational efficiency are used to improve the performance of a company. Typically, a buyout represents a change in managerial control of the company. Sometimes a buyout would occur when a public company is taken private. Buyout is the largest category of private equity.

Venture Capital – Finance provided by investors to smaller start-up firms, typically invested in an early stage company with negative cash flows that needs support until its product or service can be commercialized. Venture capital outcomes tend to be binary and are characterized by higher risk and dependent upon a small number of outsized successes. Although this type of investment 4 carries considerable risk, successes such as Facebook and Twitter demonstrate that the eventual payoff can be extremely large.

Distressed/Special Situation – Generally involves the purchase of equity or debt securities in a company that is experiencing hardship. The GP becomes actively involved in the management of the target firm, with an eye toward the potential for higher future value if the company recovers.

Expansion/Growth Capital – Typically involves minority investments in established companies with attractive growth characteristics. These companies typically maintain positive cash flow and therefore present a more stable risk/reward profile.

Figure 3: Forms of Private Equity within the Growth Lifecycle of a Company

Source: Credit Agricole